Podcast 8 James Scott

James Scott

Recorded at James Scott’s home, Heswall on the Wirral, UK on 26th September 2018

Rob Nesbitt talks to James Scott about his long and fascinating career as a player, conductor and adjudicator that spans over seven decades – a truly remarkable achievement.

From his early days listening to his fathers band at Besses o’ th’ Barn way back in 1931, and first picking up a cornet on his eighth birthday in 1933 through to adjudicating in this millennium James charts his path through the golden era of banding, playing with the greatest bands at the time, conducting and adjudicating and finally achieving an arts degree with open university at the age of 74.

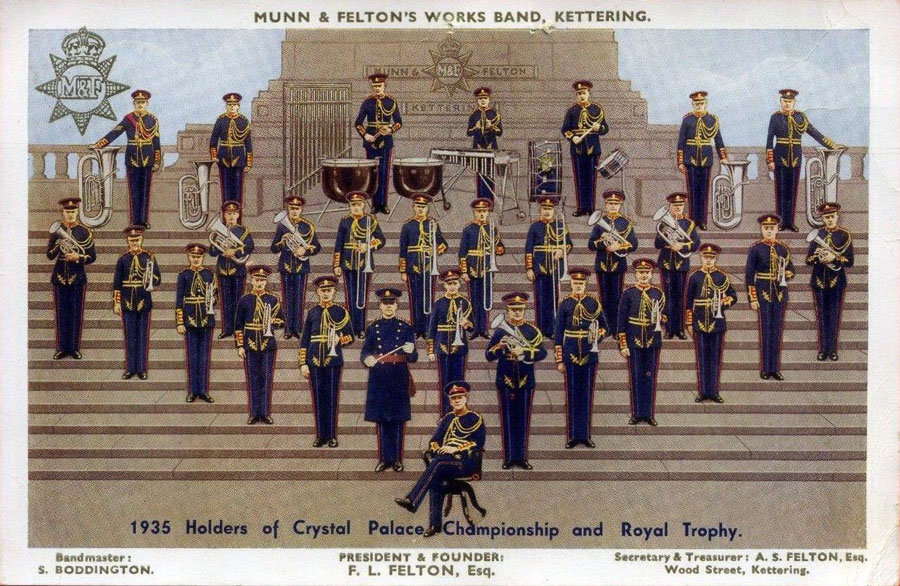

James was inspired first by the legendary cornettist Enoch Jackson and then by watching Munn and Felton, conducted by Stanley Boddington winning the National in 1935 at the Crystal Palace. He was soon to become a legendary soloist himself with the very same band he had so admired.

It was an absolute privilege to to do the interview with the man who I have always regarded as one of the very best conductors I have worked with in my own banding life. He is a true gentleman, has a charismatic personality with a great sense of humour and I know you will enjoy listening to his recollections.

This is the first part of the interview which looks at his brass banding career. The second part of the podcast, which will be posted shortly, consists of questions that listeners to the podcast have asked such as James thoughts on open adjudication and what an audition for a cornet position was like with Harry Mortimer doing the audition back in that golden age of banding!

Listen to the podcast with James Scott (Part 1) – 42 Minutes

If you would like to read the transcription of the podcast with James Scott just scroll down the page…

Transcript of the Podcast with James Scott

Rob: Hi, this is Rob Nesbitt, aka Nezzy, and this is the Nezzyonbrass podcast. This is a very special edition of the podcast, particularly for me, as I have the pleasure of talking to one of my all-time favourite conductors, the highly respected James Scott.

I first encountered him when he took Tredegar to a local band contest at Ebbw Vale in 1994. He chose John McCabe’s “Cloudcatcher Fells” as the Own Choice test, and it was the best performance I’ve ever been involved with. I’ve never seen a band elevate themselves so much, and it was all to do with the sheer charismatic approach combined with the band’s absolute respect.

I recently attended the pre-contest dinner for the British Open in Birmingham this September, kindly hosted by Martin and Karen Mortimer. One of the other guests was James Scott, and I was delighted to meet him again after such a long time. He kindly agreed for me to visit him and his lovely wife, Denise, at their home in Heswall on the Wirral. Without further ado, here is the interview.

Rob:You were born on the 29th of March, 1925 into a musical family, and one of three children, to Archie and Annie Scott at Brackley Street, Farnworth in Bolton. Archie was in the bass section of Besses o’th Barn, and you used to attend rehearsals with him. What were those early days like at home, and what were your impressions of your trips to Besses?

James: Well, first of all, I remember transport was nothing like today. In fact, I remember first going…I would be seven years old in 1932. That’s right. My dad took me…Besses were due that year to go to Canada to play the National Exhibition.

They were rehearsing on Sunday mornings. I remember once walking because there was no transport on the Sunday morning. My dad was carrying his E-flat bass on the bike. That was amazing, and it was several miles, you know.

But anyway, that was my first introduction to Besses Band. I think they’re still the same band room as far as I know. Of course, I talked to Roy Newsome [inaudible 00:02:09] Besses about this going up the stairs, and my dad sat me on a big wicker basket, couple of feet tall and very wide. And it was actually the basket that they used, when they went on world tours, for all their music. All the music was carried in it. And he sat me on that. I can see it now, the band at one end, I was sat near the door on the other end.

And they started rehearsal. The musical director hadn’t arrived. And the man who started it, his name was Samuel Pyatt, and he was the ex-principal cornet who did the world tours with Alexander Owen in the beginning of the century.

Rob: Wow.

James: Yes. That was my introduction to the band world, really, because that was the Besses o’th Barn. They were a real name in those days, of course.

Rob: Yes, they were.

James: In fact, in 1931 when I was six, they won the Belle Vue. I don’t remember the occasion, of course, except to say I distinctly remember my mother, who went to Belle Vue on that day with my aunt. They were sisters, and they came back…and I was playing in the front of my granddad’s house, and they came back and said, “Your daddy’s band has won.” And I was playing outside. So, that [inaudible 00:03:45] my introduction.

Rob: Enoch Jackson, who was the principal cornet player then…

James: Oh, he was.

Rob: And I think he had a bit of an influence on you with regard to his solo playing.

James: Oh yes, indeed. This is something else that I recall very easily. Besses Band were…I have a feeling it was the same year Besses Band…I know I hadn’t started playing, anyway. So I must have been seven. Besses Band were engaged to play in a department store in Piccadilly, Manchester. It must have been a promotion. I think it was three short programs each day for a week. Anyway, my dad took me on one of the days. I can see it now, Enoch Jackson playing a cornet solo. And he got up, no music. I’ve forgotten, unfortunately, what he played. But anyway, it was a typical triple-tongue polka, I think. But he was quite a showman, and he walked from one side of the stage to the other during the tutti’s before he started playing. No music on that set. And my father…I said, “I want to do that.” That lit the fire for me.

Rob: So, when did you get your first cornet, and who gave you your initial lessons?

James: Well, actually, it was my dad. He gave me my first lessons. And I started on my eighth birthday. I came home from school…I was near enough from school to go home for lunch in those days, so I used to run home for lunchtime. And on this day, my birthday, eighth birthday, yes, I got in the house and my dad was sitting there with a cornet in a box. I always remember, a wooden box. Not the fancy cases you get now…a wooden box. And it was a cornet. And so that was my first, on my eighth birthday. And Dad gave me my first few lessons. And after that, I had one or two lessons with one of his Besses friends, you know, cornet players. So that set me on the way.

Rob: Your first band was Ellenbrook and Boothstown?

James: That’s right, Ellenbrook and Boothstown, which was just not far down the road on the tram. I was nine then. I couldn’t have been there long about a year. My dad had left Besses by that time. He’d started running his own business, so…he was a builder.

He later became a miner. But my grandfather was a builder, you see, so Dad sort of followed his footsteps, half and half. So, my dad took me to Ellenbrook and Boothstown. I wasn’t there but about a year, I think.

Anyway, 1935, he joined Eccles Borough Band. And he took me with him. But I started having lessons with a cornet player called Clifton Jones. Famous name, he was. He played solo cornet for Irwell Springs Band, who had been the previous national champions in the ’20s, I think. And he taught me…because I remember asking him…on the first few pages of the Arban. I knew that he’d played “Carnival de Venice,” and I asked him if he’d play it for me. Of course, I’d only been playing a couple of years. And, of course, he was a very good player. He played it for me. I remember that distinctly, you know. And that was another occasion for, “I’d love to play that easy.” And all those years later with Munn and Feltons, I recorded it.

To go back to what I was getting from, Enoch Jackson, you see, this is what prompted me. I was determined I would always be a soloist, a proper soloist. In other words, playing without music. If there’s somebody who’d play a piano for half an hour, playing a whole concerto, why can’t I just play for four minutes or five minutes without…that was my view.

Rob: I’ve never looked at it that way.

James: Yes, yes. So, all these things clicked, which made me follow my dream, which was to be a soloist.

Rob: Yes, and you did it.

James: I did. I managed it in the end, yes.

Rob: It was with Eccles Band that you experienced your first Open on Dr. Keighley’s “Northern Rhapsody.”

James: Oh, yes.

Rob: I bet that was a day to remember.

James: Oh, “Northern Rhapsody,” Thomas Keighley. I was 10. I was right at the end of the line, of course, third cornet. My teacher was conducting – Clifton Jones’ Black Dyke won – Surprise!

Rob: Soon after, you took part in your first Nationals at the Crystal Palace.

James: That’s right, yes.

Rob: Again, a memorable day. Can you describe the event? And what was it like playing in the Crystal Palace, especially for a brass band competition?

James: Well, as I remember it, it was very open, similar to Belle Vue with the audience very near to you. And, of course, to a 10-year-old boy, the whole place was immense. Which it was, really, the Crystal Palace. I can just remember walking up the steps with my father and entering this vast space. And we played Pride of Race. I remember the evening concert, Fodens had won previously, three times in 1932, ’33, and ’34. So they were barred for ’35. And so, Munn and Feltons won.

I remember standing with my dad. They came onstage to do the Lap of Honor, which was done in those days. I said to my dad, “Oh, I’d love to play with that band.” Well, being a 10-year-old boy, I was probably more influenced by their wonderful uniform they had in those days. Because Munn and Felton had a unique, in those days, fully military…it was a copy of the Hussars Regiment – Austrian knots all the way across it in gold, and thick, red stripe down the trousers. And being a shoe factory, of course, Munn and Feltons, they all had shoes made at the company.

William Halliwell conducted them. They’d only been in existence two years, you know. And I said, they were started in ’33, but they got a lot of good players together. But they won on Pride of Race

I said to my dad, as I say, “I’d love to play with that band.” And, of course, 12 years later, I joined them.

Rob: That’s right.

James: I was 22 years old when I… I often wonder, I wouldn’t be surprised if I’m not the only person alive who played in the Crystal Palace, the top section, in 1935.

Rob: There won’t be many!

James: No, no.

Rob: You were on the move again at the age of 12 when your father moved to Griff Colliery in Nuneaton?

James: That’s right, yes.

Rob: And I believe you joined the Ibstock Band, which later became Desford Colliery.

James: That’s correct, yes. When I joined Ibstock, I was 13. We used to go on the bus every weekend from Nuneaton to Ibstock. Come to think of it, I used to stay every weekend. I used to go on a Saturday and stay with the euphonium player in the band. Mr. Measures. And I used to stay in his house with him and his wife for the weekend, practice Sunday morning. And I was…how old would I be? 1938…yes, 13 years old. I was Principal Cornet of Ibstock.

Rob: What section were they in?

James: I think it was third section. I think it was third section.

Rob: Ibstock’s is Leicestershire, isn’t it?

James: Leicestershire, it is. Yes.

Rob: Because my very first band was Wigston Temperance Band in 1966.

James: Leicester, yes. I have a feeling that they’re a little bit better, Wigston, because I remember…my teacher then was Thomas Underwood, who was the conductor at Ibstock. And he used to tell me about Wigston Band. They were quite a good band in those days.

Rob: Oh, I wouldn’t know. I don’t go back that far!

James: When I say good band, I mean to be at Ibstock, they were a little bit above us.

Rob: Right.

James: So, I think they were in something like the second section, you know. We were in the third section

Rob: Soon after, you were invited to join the City of Coventry Band on the end chair, age 15.

James: Yes.

Rob: Was that an enjoyable period?

James: Oh, yes, yes. I joined second man, first of all. I can’t remember, who was solo cornet. I have a feeling , whoever it was went into the army, and so I moved up to the end chair. George Thompson was the conductor in those days. And I remember we went to Belle Vue when we…was it 1940 or ’41? ’41, perhaps, we went to Belle Vue. But we were third, at the first attempt.

I also did, around that time, City of Coventry did the very first broadcast, which I remember very well. Went to Birmingham, the BBC Studios in Birmingham in those days was in Corporation Street. Why I remember the Corporation Street I don’t know!

The very first broadcast, I remember the overture we played, but I cannot remember the name of it. I could play it with the cornet, …if I could play the cornet, which I can’t. I can’t play at all now.

Rob: Oh, no.

James: The last time I tried was a couple of years ago, and I put it down in disgust.

Rob: Oh, dear.

James: The only thing I do now, about once a year, I get the trumpet and the cornet out, open the case, grease the slides, make sure the ferrules work properly, you know, not too tight, and put them back in the case. That’s all.

Rob: Coming back to Coventry, George Thompson left Coventry to take over at Grimethorpe, and you followed. You moved around quite a lot in those early years. It was at this point you had to leave home to be in Grimethorpe. What was that like?

James: Actually, I didn’t really want to go. But I was 16 and, in those days, did what my father wanted me to do. But anyway, that’s not to say I didn’t enjoy my days. George Thompson asked my dad if he wanted me there, and my dad said, “Yes. He can go,” you know. So off I went to Grimethorpe. That was, obviously, the best band I’d played up to that point.

Rob: Yes, you were bumper-up there, to start.

James: I was bumper-up through a guy called Wyn Moore. I never actually played as a stand-up soloist while I was at Coventry. But that was my start, with Grimethorpe. I remember the first solo I ever played, and I remember where I played it, with Grimethorpe, that is, in York. on a Sunday afternoon, and I played ‘Il Bacio’. That was the first time I’d played a stand-up solo, and I worked and I worked to get it from memory, and I was determined I was going to play without music. So, I played at Grimethorpe, I think it was 1945, the year the war ended.

We played at the very first Brighouse Mass Band concert that was organised. And, of course, that’s a famous venue at Huddersfield Town Hall. I always remember, Dennis Wright conducted. Or was it Eric Ball? Could have been Eric Ball. And the three bands were Brighouse, of course, Wingates, and…Grimethorpe.

And I also played on the second one in 1946. There was a young boy who played a cornet solo for Brighouse. And he played “Oldest City,” and his name was Derek Garside. And he was 15 years old. I remember it very clearly. And he had a lovely sound. And the rest, as they say, is history as far as Derek’s concerned. That was my first meeting with Derek Garside.

Rob: In 1947, you were on the move again, and you joined the band you so admired when they won the 1935 Nationals at the Crystal Palace, Munn and Feltons, with musical director Stanley Boddington. Again, you went in on the assistant principal seat but moved up to the end seat. This was becoming a habit. Could you describe your audition to join the band, the job that went with it, and what was it like working with Stanley Boddington?

James: This is rather amusing. My audition was in the factory. Mr. Fred Felton was present and Stanley Boddington. You’d never believe what he asked me to play. He said, “James, I want you to play me the National Anthem”. He actually said, “Will you play me the National Anthem?” “Oh, of course, I just played it. And he had his reasons, of course. And I thought since, “Yes, he just wanted to see how I played something slow-ish, to start with.” Then he said, “Now play something… what would you like to play an air varie?” And then I started playing “Carnival de Venice.” And I just played it with no music, of course. And he put up two or three things, sight reading, which I never had any trouble sight reading.

So then I had a private interview with Mr. Fred Felton, who was the boss. And he said, “Now then, James, Mr. Boddington tells me he’s quite happy with you, and he’d like you to join us. What do you do?” “Well, I have worked in an office.” “Yes well, I’m going to put you…if you come here, I’m going to put you in our leather room.”

That’s where I started. I eventually ended up in the office where I did a job in the office. But I started off in the leather room, which was the room where they had shelves full of leather, rolls of leather, some of it calf leather, which was made for the best shoes, of course. Lovely leather and I spent a few months there.

But eventually, I ended up in there. And as far as being bumper-up, yes, I was bumper-up. You see, I had a different view and I’ve always had this view, so I was second man. So what? I was interested in solo playing. And I didn’t see why there was a problem about…I was in the second chair. So, it became a habit for me to play solos.

The solo cornet player was Joe Higgins, who was a good player, very good player, good sound. And I spent some years just sitting there. But Stanley gradually made me into the soloist, the stand-up soloist. And then that had been my ambition since I was seven years old, when I saw Enoch Jackson. And I finally made it.

You see, I always had this view, “So I’m second man, so what?” I was the featured soloist. When I think about bands like the big band business, bands like Stan Kenton who were world-class bands, they had four trumpet players. They were all soloists, you know. Why can’t I be the same and the best man? Of course, we all know why – there are that many top class players. But I didn’t see why there was a problem with it.

Rob: What was the discipline and punctuality and dress code like at Munn and Feltons?

James: It was a different world. You could not imagine. We used to say, “There’s only one excuse for not attending. That’s if you were dead.” Yes. This was the real days of company bands. It was your job to be at rehearsal. Yes, had to be. And I always remember, we used to have to go up the stairs, and there was a canteen there they used for rehearsals. There was a clock at one end, and when I first went to Munn and Feltons clock, I had a little plaque underneath it, black and white. And it said in printed letters, big, printed letters, “Always on time, harmony sublime.”

Rob: That’s brilliant. There’s a few conductors about now who should have a clock like that in the band room.

James: “Always on time, harmony sublime.” And that was still in place…that had been there since before the war, I was told. But it was still in place then. It didn’t last, because we had another band room. It was very clear

Rob: What was the band’s concert and contest schedule like? You were away all the time or…

James: As far as concerts were concerned, winter months, we didn’t do all that much work like a lot of bands are now. The winter is the concert season, virtually, for top-class bands. Those days it was a little bit different. We did travel before motorways, but the real traveling was done in the summer months. As a matter of fact, the year that I joined Munn and Feltons, 1947, the band were away for 8 weeks, and in 1948, the following year, 10 weeks.

Rob: Good grief.

James: But that was my first two years. ’47, and we were away for eight weeks. Played for a week. in Worthing and then two weeks in London, Hyde Park. And then we would go up to Scarborough, we were out there a couple of weeks in Scarborough playing on the lake, Peasholm Park. Glasgow for a week, Dunfirmline for a week. Edinburgh Princess Street Gardens for a week. Well, this is continuous.

Rob: You must have had a lot of downtime as well, then. You’re not playing all the time, and if you’re away for weeks on end…

James: Oh yes, that’s right. Mornings invariably…except for Scarborough. At Scarborough, you had to play three times a day. Morning, afternoon, and evening. So the day was spent moving band equipment around. In Scarborough, we would play on the bathing pool, in the South Bay in the morning, and then all the equipment had to get to Peasholm Park for the afternoon and evening. And then the coach would go around dropping people off for the digs, because we all had our own digs.

I remember there was four of us used to stay with a lady who was from Northamptonshire. That’s probably why we stayed there, because we were from Northamptonshire. We used to have to nip home for lunch, back down to the park, afternoon concert. And then on Saturday evening, we didn’t have a concert because the council took the view it was a change-around as it was in those days.

Rob: Oh, right. Yes.

James: Saturday, nobody went on holiday except on Saturday in those days. So we had a Saturday evening off. That band, they could play anything. They were like a machine. While we were in London, I remember once, Harry Mortimer came along because he used to visit us occasionally in those days. And we did a broadcast, and we were still being told what we were going to do as far as repeats or no repeats. In other words, he’d come in cold, and that was was live. We’re not talking about recordings. No, that was a live broadcast. And he was saying, “I will watch the clock. If I do this (Makes gesture with hand), you don’t repeat.”

Rob: That puts the edge on it a bit, didn’t it?

James: Yes. That was the way they did things, we did things in those days. Of course, we’d been together for so long, he had the faith of the band to do it. And you cannot imagine it now.

Rob: No, I wouldn’t want to imagine it!

James: Yes.

Rob: And there was an incident when the band were playing under a marquee in Plymouth in really bad weather, on a problem with a bus.

James: Oh, yes. In Plymouth Ho and and on the Sunday our first concert in Scarborough. So, in fact, we were due to travel through the night to report for duty, as it were, in Scarborough. Imagine that.

This is before the motorways. This is the kind of traveling we used to do. I remember very clearly, we had our meal on the Saturday night, loaded the coach after the concert. We’d been warned that there’s some bad weather approaching. Up to then, the weather was all right.

We started on our journey. It was a series of mishaps, because the band’s coach just outside Exeter, the brakes failed, and we were going…I can remember now Stan Boddington was sitting right at front of the coach, and he was telling the driver, “Why don’t you just…” because we were on a country road, hedges at each side, “…drive into the hedge to try and stop,” which he did.

Well, to cut a long story short, fortunately, there were no injuries or anything. He managed to stop the coach. And the boss, he used to sometimes visit us, which he had done that day. When i say the boss i mean Mr Felton in his Rolls Royce. And he went ahead and found a hotel in Exeter.

They had no room, but they allowed us to sleep on the dining room floor. Would you believe? The band to actually kipped down on the dining room floor of this hotel in Exeter. And he had to telegraph ahead to cancel at Scarborough to say, “We’re very sorry.”

Now, on that same Saturday evening, of course the weather was very bad, there was a terrific wind, and we’d been playing in a marquee in Plymouth Hoe. It blew the marquee into the sea. And so, we’d only played a concert there a few hours before. We’d learned that when we were in Exeter in the hotel. So, we had to miss our first concert in Scarborough the next day, which was the Sunday.

Rob: You retired from playing after winning the National Solo Championships of Great Britain in 1959 and 1960. Why did you decide to finish your playing career when, really, you were at the top of your game?

James: Yes, that’s true, I was. Well, you know, I’d been in company bands since I was a boy. Somehow, I had this feeling…I’d seen what happens, which is really you spend your life playing for a company band. If you’re on an end chair or you’re a soloist, the day inevitably comes in declining a better day, and you start sliding down the line.

And another thing, I’d played under Stanley Boddington for so long, I’d played under Harry Mortimer. I’d always had this view, “Listen, look, and keep this closed…your mouth closed.” And I’d always done that, you know. And I thought, “Yes, I think I would like to do that (conducting). I think perhaps I might be able to do that.” So all these things combined, “Now, what am I going to do?” I didn’t just walk out and start conducting.

I had a letter one day, the year I’d won the National Solo Championship for the second time, 1960. I knew it was from the Managing Director of the ship building company at Cammal Laird’s wondering if I’d be interested in talking to them.

They were looking for a bandmaster. I actually phoned them, and they said, “Yes, we’re looking for a conductor. We’re only in the third section our conductor is Rex Mortimer. He’s a professional. Come and see us.” So, I did go and see them. And I met Rex, and I talked to him. I was just going as the bandmaster. Anyway, it all happened that way. And everybody thought I was crazy. “What on earth are you thinking of doing?” You know.

I remember Harry Mortimer saying to me, “James, remember…” no, no. Not James, Jimmy. He always called me Jimmy. He said, “Jimmy, all that glistens is not gold. Remember that.” I said, “Yes, I know.” But I felt that somehow this was right for me to do, and I wanted to conduct, I decided to up sticks and go, which I did.

But, of course, I worked like a madman, I must say, at Cammel Laird. I was determined. Once or twice, I thought, “What have I done?” But it worked out. And I was only there about a year and we won the third section and got into the second section. Rex then left because, I think something had been said at Fodens you know ‘When it gets to the top section we don’t want this band interfering”.

But anyway, Rex left, and so I continued working, and got in one or two better players. And we won the area and in 1964 when I first attempted the Royal, the Albert Hall. We were fourth on Variation on a ninth/

Rob: That’s good result.

James: And then in 1965, runners up to Fairy they won on Triumphant Rhapsody We were second. So it worked.

Rob: And your most successful national result as a conductor came with Brighouse and Rastrick. I’d imagine it was a joy to work on Hubert Bath’s “Freedom”?

James: Oh, it was. We did quite a lot of section of rehearsals as people do. So, as a matter of fact, I had a visit a couple of weeks ago from Les Beevers, who was chairman in those days, and Garry Cutt.

Garry Cutt worked with me when he was a young man he’s in his 50s now, but a successful young conductor. They visited me, Les and Garry, as they do from time to time. Les was saying, “Is it right that when you did rehearsals on ‘Freedom,’ sectional rehearsals, you got your cornet out and played for them?” I said, “Well, actually, yes I did.” He said, “I heard all about it” he said, “about you opening your briefcase and bringing this little cornet out.”

We worked very hard on “Freedom.” And Les reminded me, when he came to see me, it came together only a couple of days before the Albert Hall. Not for the first time, of course. These days things are not going so well. Then suddenly,the cogs see to get together, and it worked. And, of course, on the day it certainly did work.

Rob: Yes.

James: Yes. It was a very, very good performance.

Rob: You ventured into adjudication, the year Cory won the National Treble in 1984 was the first time you were invited to adjudicate to the Nationals alongside William Relton and David Willcocks. What was that like for you? And, as a point of interest, what is it really like in the box, acoustically, in the Albert Hall?

James: I remember Sir David was a charming man, very straightforward. He was a delightful man, I thought. As a matter of fact, he was head of the Royal College of Music when my wife was there. Yes. So, well, that’s another story. But I remember starting adjudicating, like I did with conducting. I started at the bottom. Peter Wilson was Editor in those days. And after theband had won, Peter said to me, “I think you should start adjudicating.” I said, “No, no, no. I’m not really bothered, Peter.” I said, “I’ll do another few years.” He said, “No, I really think you should…”

Anyway, he persuaded me. And I’ll always remember that very first adjudicating that I ever did was the second section in the northern area. And that was the first one I ever did. So then things snowballed a little bit. And, yes, I ended up first time adjudicating at the Albert Hall.

Acoustically, I never had a problem. I’ve always said, “Whatever the circumstance, the cream will rise to the top.”

Rob: I’m gonna go back to your conducting now. If I mention Peasholm Park as a conductor, does it bring back a soggy memory?

James: Yes [laughing]. We had a band sergeant. Of course, he was responsible for general discipline. Arthur Heath was his name. He was one of the bass players. Because we had to row from the landing stage over to the bandstand at Peasholm Park, I think that there was a couple of rowing boats.

I know it’s crazy when you think about it. But it’s still there as far as I know, because the bandstand is in the water, so we were rowed out half an hour to get the band on the stage. We were rowed out with a couple of these rowing boats. Of course, you had to be careful. You were stepping out of the side of the boat onto the stage.

The danger was always obvious, to be careful. For some reason, it had to be me. But as I went to step onto the stage, something happened. I always had my suspicions. But something happened, and it just gradually moved away, and my foot went straight into the water, down. Fortunately, it was only a couple of feet deep, but that was enough. I ended up with both legs in the water up to my knees.

Rob: The Kings of Brass was a happy seven years of your life. Who came up with idea, and what was the criteria for membership?

James: Yes. Actually, that seven years was a joy.

Rob: I bet.

James: An absolute joy. Anyway, it was in 1994, I got a call from Les Beevers, and he said, “Jim, how would you like to conduct a band called the Kings of Brass?” “Yes,” I said, “I have to say yes. Sounds interesting.” So he went on, and he said, “Well, you know, you know the Navigation Inn in Saddleworth, which is what we always used to use as the brass band. And, in fact, I know that in those days, a few players from Dyke, a few players from Brighouse. They would very often meet up there, some would be on the way home after rehearsal.

In fact, the landlord was Ian Gibson who now lives in Spain and has done for seven years. But he was the landlord, cornet player, you know. It was the brass brand pub, in other words.

So, Les, Geoffrey Whitham, Brian Evans, soprano player several players of that ilk, you know. Either played with Brighouse or had played with Brighouse. They were together once in the Navigation Inn. They were talking, as I’m sure, as everybody knows, all of the country that talked about, “How about such and such a player? What do you think?”, “He’s still around. He’s still playing with Geoffrey.” what about that the band? He played with Faireys, he played with Brighouse, he played with Dyke. Then we could have a good band, couldn’t we? . I believe it was Brian Evans the soprano player that said.” “Wait a minute, why don’t we do it?” So that was the beginning of the Kings of Brass.

They talked about it, and they said, “Who shall we ask” why they’re running around all the names, ex Dyke ex Brighouse, Munn and Feltons. Our two trombone players from Munn and Feltons. Maxwell Thornton, who was first trombone in my day. Then Les rang me.

So, it was all raised. We had an initial rehearsal. The criteria, it obviously had to be very good players, still playing well but not necessarily in any of the bands, you know. We were supposed to be a veteran’s band. I think the youngest was late 30s, but mostly they were all 50s and 60s. They had to be the right type we all knew.

Rob: As a youngster, you earned a few academic qualifications but decided to study at the Open University with a degree in art at the age of 69.

James: Yes.

Rob: This had me intrigued. What made you decide to do this?

James: Well, I’d left school at 14, as we did in those days. No qualifications. In other words, it was virtually an elementary education and so throughout my adult life, I’d always that I missed out on an education, which I had, no doubt about it. I mean, music was my saviour.

After I retired, I sat here one day reading the paper and saw the Open University advert. And I though, “Right, I’m going to do something about this.” I don’t want to go into music. I’ve spent my life in music. So I sent off for the pack. And I thought, “Now, art, humanities. I think I will go for that.” European history and literature as back as far as, Shakespeare.

And I think the last year, I always remember the last year, was spent in democracy and the state, and it was about 80 degrees. And that was the last year, the fifth year I did. So then, yes, I got through it all right. And when I was 74, I graduated.

End of part 1 of the podcast transcription

The second part of the podcast, in which I ask James Scott your listener questions and some that I have chosen will be published shortly

If you would like to be kept updated with new podcasts and articles and have automatic entry into future prize draws please sign up to the Nezzyonbrass Newsletter here..